THE BLUE SERIES

THE FINGER, 2019 (OIL ON CANVAS, 5' X 6')

BLACK FAMILY IN TIMES OF STRUGGLE, 2017 (OIL ON CANVAS, 40" X 60")

Credit must be given to Ta-Nehisi Coates' book, "The Beautiful Struggle" for this painting. I attempted to conglomerate the figures in a family. Strong color gives emotional content to their thoughts and aspirations. The American flag entanglement portrays their struggles.

THE AMERICAN FLAG ENTANGLEMENT

PORTRAYS THE STRUGGLE OF THE BLACK FAMILY

FIRST FAMILY OF COLOR, USA, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 30" X 36")

This painting called out to become an abstract painting after several years and several layers of paint. The canvas’s surface was pockmarked with tree bark-like fissures and scratches, not the eggshell smooth surface preferred by academic portrait artists. With its own emotional struggle, it was the perfect broken canvas to recreate the first family of the USA in the same frame with color and mystery, and to poke a little fun at the all too serious portrait artists, Kehinde Wily and Amy Sherald at the same time. The artistic origin in this work can be found in Davinci’s “Mona Lisa” and in African sculpture.

THE PERFECT BROKEN CANVAS TO RECREATE THE FIRST FAMILY OF THE USA

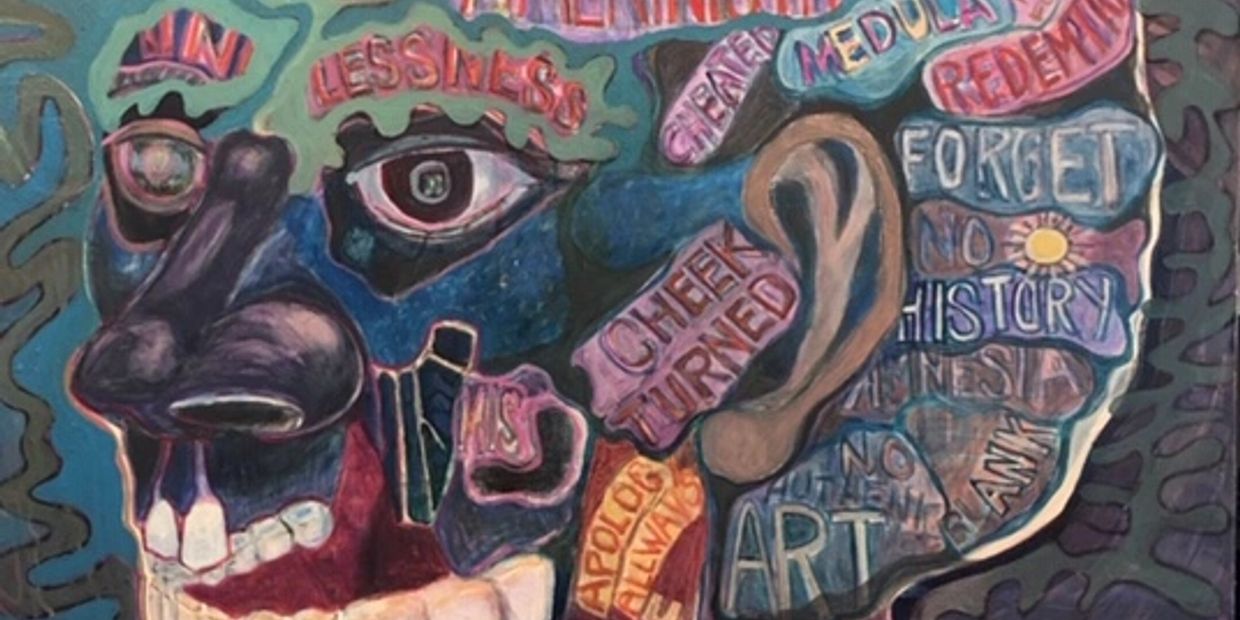

AFROAMNESIA, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 40" X 60")

RESTING UNDER THE LYNCHING TREE, 2016 (OIL ON CANVAS, 40" X 60")

The seventy-pound Mississippi cotton gin fan wrapped around the body of Emmett Till, the truck tire prints embedded in the skin of James Byrd Jr. after being dragged and run over in Jasper, Texas, and the often beautifully moss-draped trees with lynched bodies hanging from their limbs in the south was the inspiration for this painting. The resting figure is symbolic, though, of the mindset of a black man who must live and work in the shadows of the tree as if the tree and its evil purpose did not exist at all. It is a restless rest. Inspiration for the resting figure can be found in African sculpture.

THE MINDSET OF A BLACK MAN WHO MUST LIVE AND WORK IN THE SHADOWS OF THE TREE

MOCKING BIRD UNDER THE GAZEBO, 2016 (OIL ON CANVAS, 48" X 60")

Harper Lee’s mockingbird is not the bird I had in mind. It is commonly agreed that Lee’s mockingbird was code language for how to kill a negro and get away with it, because no southern white court would consider the murder any more serious than killing of a bird. The worst penalty to be expected was maybe a little bad luck, which one could endure with a little help from the white community. The painting’s main elements are four symbols of racial struggle.

CODE LANGUAGE

FOR HOW TO KILL A NEGRO AND GET AWAY WITH IT

MICKEY MOUSE JUSTICE, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 48" X 72")

This painting’s composition is staged as if it were an opera. The characters sing out or act out the injustice done to a black youth whose baby face belied a barely budding black manhood. “How can this be ‘justifiable homicide?’” asks Mickey Mouse. This oil painting is visual art imitating performance art. For sense of place, the painting has a gazebo, now another sign of a benign structure being a place of potential death for black youth.

HOW CAN THIS BE

JUSTIFIABLE HOMICIDE?

PROPHETS AND PRIESTS, 2017 (OIL ON CANVAS, 30" X 40")

KATRINA, 2014 (OIL ON CANVAS, 8' X 15')

Katrina as a subject has been explored by me since 2012. This painting is the last of a series. The first notice received about Katrina was from the Toronto Star in 2010 while I was traveling in Ontario. The Canadian reportage could not have been more different from how the catastrophe was written about in the states. Three smaller paintings of Katrina are at the Safe House Black History Museum in central Alabama.

THE CANADIAN REPORTAGE COULD NOT HAVE BEEN MORE DIFFERENT THAN HOW IT WAS WRITTEN ABOUT IN THE STATES

HANDS UP DON'T SHOOT, 2017 (OIL ON CANVAS, 24" X 78")

I had been thinking about the criminal justice system and the criminalization of our youth for the smallest infraction for quite some time. Somebody gave me this odd shaped, ripped canvas, which had enough good surface to one day make a painting. It was stored away near the trash bin with an old “Wanted” poster - the kind you find in your local Post Office. The odd shaped canvas appeared to be the right shape for a “line up” of these youthful offenders, all with little hands and quizzical faces. The criminalization of our youth can start as early as the first grade. The painting is meant to ask the question: if these kids of color are criminals, why is there is no corresponding criminalization of white youth of the same age? The drawing was kept simple like that that of Jean-Michel Basquiat’s India-blue colored deities.

THE CRIMINALIZATION OF OUR YOUTH CAN BE AS EARLY AS THE FIRST GRADE

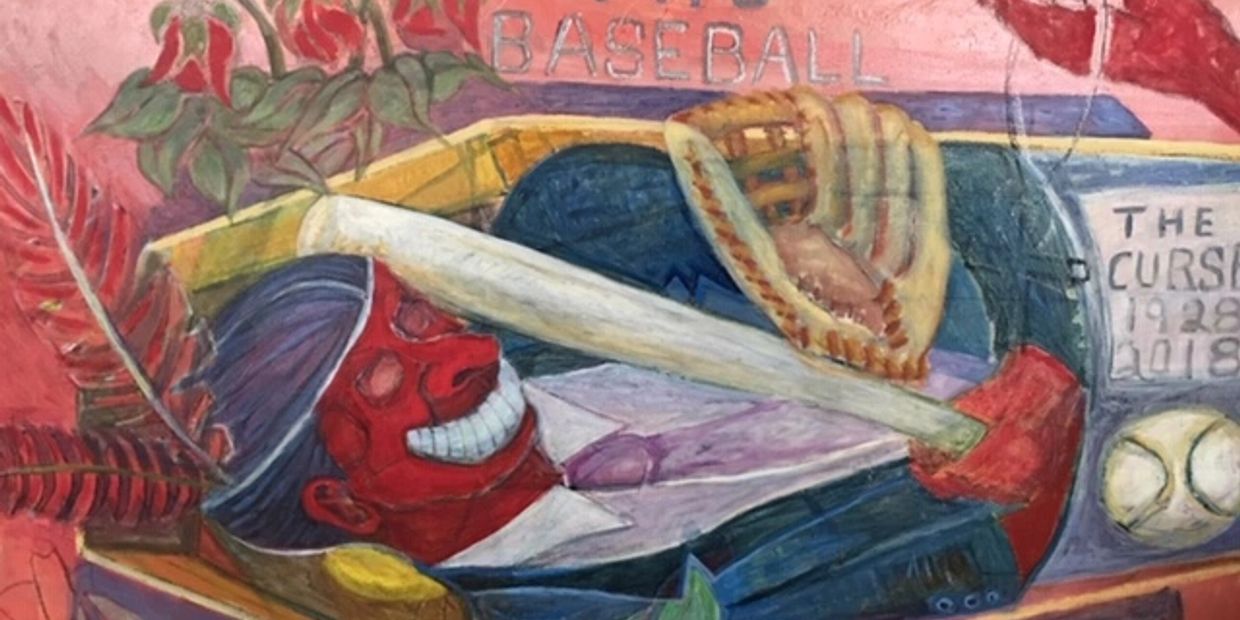

CURSE IN A COFFIN, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 52" X 80")

I’ve been examining Chief Wahoo, usually with angry fangs and horns, for the past ten years. After nearly a hundred years, the smiling mascot image of the Cleveland Indians is being discontinued at the end of this year. The caricature of a big-nose red-faced American Indian was of little concern, until I began to understand the power of mis-characterized and dehumanized racial images. American people of color face such ubiquitous negative images in their visual field constantly. The painting portrays Chief Wahoo’s perspective as happy that his restless soul his finally being put to rest in Cleveland, Ohio, along with his ball, bat, and catcher’s mitt.

I BEGAN TO UNDERSTAND THE POWER OF MIS-CHARACTERIZED AND

DEHUMANIZED RACIAL IMAGES

TWENTY MILLION DOLLAR SPECTACLE, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 40" X 60")

This is a striking symbolic adaptation of an actual event that has been viewed subliminally for a few seconds, each tens of millions of times, without a blink of an eyelid on national television. It is a visualization of “The Forty Million Dollar Slave,” a book written by William C. Rhoden in 2006. The picture frame contains three surreal elements: a black athlete with a football and a white female. Each element is integral to a masculinity that generates revenue to support universities and the professional salaries of coaches, while the athlete’s remuneration is less than food stamp value. At another level, it speaks of educational misdirection, dominance, ownership, and exploitation of black masculinity at all strata of our capitalistic society.

EXPLOITATION OF BLACK MASCULINITY AT ALL STRATA OF OUR CAPITALISTIC SOCIETY

THE PRICE OF FREEDOM, 2017 (CANVAS ON OIL, 52" X 60:)

Inspired by Ta-Nehisi Coates, I wanted to show the importance of knowing what unites people of African descent in the New World of the Americas - north, south and the black Carribean. Important symbols of the Confederacy and Haitian history and its opposition to slavery are symbols of neo-slavery in the form of a parking meter. Our history coupled with the meter from contemporary times is the paradox.

HISTORY COUPLED WITH THE METER FROM CONTEMPORARY TIMES IS THE PARADOX

BLOODY SUNDAYS, 2014 (OIL ON CANVAS, 48" X 60")

The content of this painting came to my attention as far back as 1960 while I was a high school student. It was the vision of unarmed black people, women and children, being confronted with overwhelming force. I was weighing Mahatma Ghandi and Reverend Martin Luther King's doctrine of non-violent resistance against Black Nationalist armed resistance doctrine. At that time, I painted bucolic landscape wall murals after the European Masters, as I had been taught in art school. As the number of Sundays of fires, blood, and flames increased over the past 50 years, landscapes appeared useless. It was then that Sundays, the day of rest, painting materialized. The Selma Alabama Edmund Pettus Bridge,as a symbol of where black self-determination met overwhelming radicalized force, and the ensuing struggles, seemed the perfect starting point to create this art.

A symbol of where black self-determination met overwhelming radicalized force

THE COFFIN, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 30" X 40")

This is the first painting done in response to Dana Schutz's 2017 "The Open Casket." Credit is given to Ms. Schutz for provoking the reaction that allowed me to bring this painting from my subconscious into reality. Ms. Schutz's painting is based on an appropriated image of the murdered 15-year-old Emmett Till. "The Coffin" is a symbolic representation of all murdered black men, unnamed, at the hands of self-deputized Europeans, and the family and community left behind to mourn and grieve their losses. Sad to say, I had to start another coffin painting today.

A symbolic representation of all murdered black men, unnamed at the hands of self-deputized Europeans

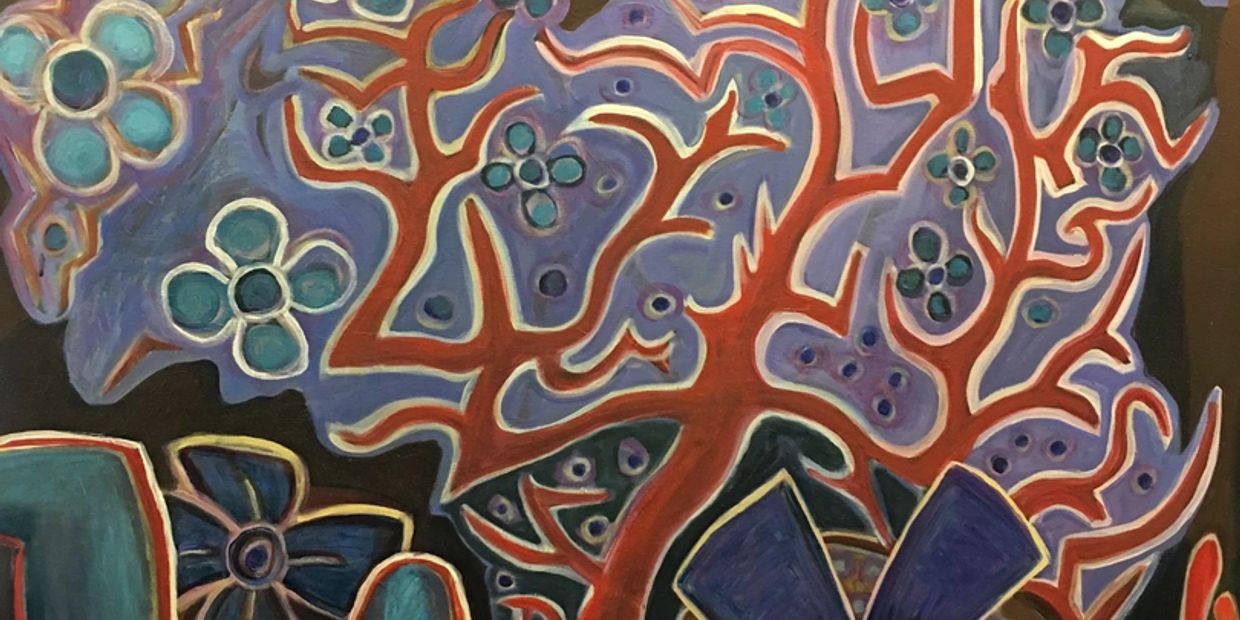

THE BLUE HISTORIAN, 2016 (OIL ON CANVAS, 40" X 60")

the prophet ponders the paradox, 2017 (OIL ON CANVAS, 32" 40")

CURRENCY UNLIMITED, 2018 (OIL ON CANVAS, 18" X 72")

The painting is a fusion of symbols with a temporal dynamism stretching from the pyramids, to the Selma Bridge, to black brain power to space exploration. It is about the use and development of the mind and imagination to make a way in this word, rather than a reliance on European systems of thought. It's about seeking magic through your “third eye,” known centuries ago by our African ancestors. The painting grew out of the fusion of African American history and the current issue around putting the face of an African American woman on the twenty- dollar bill.

It's about seeking magic through your "third eye," known centuries ago by our African ancestors.